Group 4 - Experimental Sciences

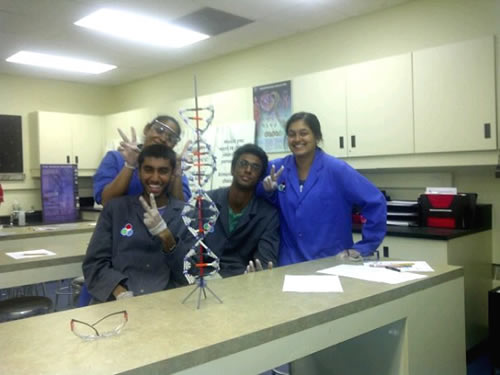

Biology – Standard Level

Biology is the study of life. The first organisms appeared on the planet over 3 billion years ago and, through reproduction and natural selection, have given rise to the 8 million or so different species alive today. Estimates vary, but over the course of evolution 4 billion species could have been produced. Most of these flourished for a period of time and then became extinct as new, better adapted species took their place. There have been at least five periods when very large numbers of species became extinct and biologists are concerned that another mass extinction is under way, caused this time by human activity. Nonetheless, there are more species alive on Earth today than ever before. This diversity makes biology both an endless source of fascination and a considerable challenge.

Biology is the study of life. The first organisms appeared on the planet over 3 billion years ago and, through reproduction and natural selection, have given rise to the 8 million or so different species alive today. Estimates vary, but over the course of evolution 4 billion species could have been produced. Most of these flourished for a period of time and then became extinct as new, better adapted species took their place. There have been at least five periods when very large numbers of species became extinct and biologists are concerned that another mass extinction is under way, caused this time by human activity. Nonetheless, there are more species alive on Earth today than ever before. This diversity makes biology both an endless source of fascination and a considerable challenge.

An interest in life is natural for humans; not only are we living organisms ourselves, but we depend on many species for our survival, are threatened by some and co-exist with many more. From the earliest cave paintings to the modern wildlife documentary, this interest is as obvious as it is ubiquitous, as biology continues to fascinate young and old all over the world.

The word “biology” was coined by German naturalist Gottfried Reinhold in 1802 but our understanding of living organisms only started to grow rapidly with the advent of techniques and technologies developed in the 18th and 19th centuries, not least the invention of the microscope and the realization that natural selection is the process that has driven the evolution of life.

Biologists attempt to understand the living world at all levels using many different approaches and techniques. At one end of the scale is the cell, its molecular construction and complex metabolic reactions. At the other end of the scale biologists investigate the interactions that make whole ecosystems function.

Many areas of research in biology are extremely challenging and many discoveries remain to be made. Biology is still a young science and great progress is expected in the 21st century. This progress is sorely needed at a time when the growing human population is placing ever greater pressure on food supplies and on the habitats of other species, and is threatening the very planet we occupy.

Chemistry – Higher Level

Chemistry is an experimental science that combines academic study with the acquisition of practical and investigational skills. It is often called the central science, as chemical principles underpin both the physical environment in which we live and all biological systems. Apart from being a subject worthy of study in its own right, chemistry is a prerequisite for many other courses in higher education, such as medicine, biological science and environmental science, and serves as useful preparation for employment.

Earth, water, air and fire are often said to be the four classical elements. They have connections with Hinduism and Buddhism. The Greek philosopher Plato was the first to call these entities elements. The study of chemistry has changed dramatically from its origins in the early days of alchemists, who had as their quest the transmutation of common metals into gold. Although today alchemists are not regarded as being true scientists, modern chemistry has the study of alchemy as its roots. Alchemists were among the first to develop strict experimentation processes and laboratory techniques. Robert Boyle, often credited with being the father of modern chemistry, began experimenting as an alchemist.

Despite the exciting and extraordinary development of ideas throughout the history of chemistry, certain things have remained unchanged. Observations remain essential at the very core of chemistry, and this sometimes requires decisions about what to look for. The scientific processes carried out by the most eminent scientists in the past are the same ones followed by working chemists today and, crucially, are also accessible to students in schools. The body of scientific knowledge has grown in size and complexity, and the tools and skills of theoretical and experimental chemistry have become so specialized, that it is difficult (if not impossible) to be highly proficient in both areas. While students should be aware of this, they should also know that the free and rapid interplay of theoretical ideas and experimental results in the public scientific literature maintains the crucial link between these fields.

The Diploma Programme chemistry course includes the essential principles of the subject but also, through selection of an option, allows teachers some flexibility to tailor the course to meet the needs of their students. The course is available at both standard level (SL) and higher level (HL), and therefore accommodates students who wish to study chemistry as their major subject in higher education and those who do not.

At the school level both theory and experiments should be undertaken by all students. They should complement one another naturally, as they do in the wider scientific community. The Diploma Programme chemistry course allows students to develop traditional practical skills and techniques and to increase facility in the use of mathematics, which is the language of science. It also allows students to develop interpersonal skills, and digital technology skills, which are essential in 21st century scientific endeavour and are important life-enhancing, transferable skills in their own right.

Physics – Standard Level

“Physics is a tortured assembly of contrary qualities: of scepticism and rationality, of freedom and revolution, of passion and aesthetics, and of soaring imagination and trained common sense.” Leon M Lederman (Nobel Prize for Physics, 1988)

Physics is the most fundamental of the experimental sciences, as it seeks to explain the universe itself from the very smallest particles—currently accepted as quarks, which may be truly fundamental—to the vast distances between galaxies.

Classical physics, built upon the great pillars of Newtonian mechanics, electromagnetism and thermodynamics, went a long way in deepening our understanding of the universe. From Newtonian mechanics came the idea of predictability in which the universe is deterministic and knowable. This led to Laplace’s boast that by knowing the initial conditions—the position and velocity of every particle in the universe—he could, in principle, predict the future with absolute certainty. Maxwell’s theory of electromagnetism described the behaviour of electric charge and unified light and electricity, while thermodynamics described the relation between energy transferred due to temperature difference and work and described how all natural processes increase disorder in the universe. However, experimental discoveries dating from the end of the 19th century eventually led to the demise of the classical picture of the universe as being knowable and predictable. Newtonian mechanics failed when applied to the atom and has been superseded by quantum mechanics and general relativity.

Maxwell’s theory could not explain the interaction of radiation with matter and was replaced by quantum electrodynamics (QED). More recently, developments in chaos theory, in which it is now realized that small changes in the initial conditions of a system can lead to completely unpredictable outcomes, have led to a fundamental rethinking in thermodynamics. While chaos theory shows that Laplace’s boast is hollow, quantum mechanics and QED show that the initial conditions that Laplace required are impossible to establish. Nothing is certain and everything is decided by probability. But there is still much that is unknown and there will undoubtedly be further paradigm shifts as our understanding deepens.

Despite the exciting and extraordinary development of ideas throughout the history of physics, certain aspects have remained unchanged. Observations remain essential to the very core of physics, sometimes requiring a leap of imagination to decide what to look for. Models are developed to try to understand observations, and these themselves can become theories that attempt to explain the observations. Theories are not always directly derived from observations but often need to be created. These acts of creation can be compared to those in great art, literature and music, but differ in one aspect that is unique to science: the predictions of these theories or ideas must be tested by careful experimentation. Without these tests, a theory cannot be quantified. A general or concise statement about how nature behaves, if found to be experimentally valid over a wide range of observed phenomena, is called a law or a principle.

The scientific processes carried out by the most eminent scientists in the past are the same ones followed by working physicists today and, crucially, are also accessible to students in schools. Early in the development of science, physicists were both theoreticians and experimenters (natural philosophers). The body of scientific knowledge has grown in size and complexity, and the tools and skills of theoretical and experimental physicists have become so specialized that it is difficult (if not impossible) to be highly proficient in both areas. While students should be aware of this, they should also know that the free and rapid interplay of theoretical ideas and experimental results in the public scientific literature maintains the crucial links between these fields.

At the school level both theory and experiments should be undertaken by all students. They should complement one another naturally, as they do in the wider scientific community. The Diploma Programme physics course allows students to develop traditional practical skills and techniques and increase their abilities in the use of mathematics, which is the language of physics. It also allows students to develop interpersonal and digital communication skills which are essential in modern scientific endeavour and are important life-enhancing, transferable skills in their own right.

Alongside the growth in our understanding of the natural world, perhaps the more obvious and relevant result of physics to most of our students is our ability to change the world. This is the technological side of physics, in which physical principles have been applied to construct and alter the material world to suit our needs, and have had a profound influence on the daily lives of all human beings. This raises the issue of the impact of physics on society, the moral and ethical dilemmas, and the social, economic and environmental implications of the work of physicists. These concerns have become more prominent as our power over the environment has grown, particularly among young people, for whom the importance of the responsibility of physicists for their own actions is self-evident.

Physics is therefore, above all, a human activity, and students need to be aware of the context in which physicists work. Illuminating its historical development places the knowledge and the process of physics in a context of dynamic change, in contrast to the static context in which physics has sometimes been presented. This can give students insights into the human side of physics: the individuals; their personalities, times and social milieux; their challenges, disappointments and triumphs.

The Diploma Programme physics course includes the essential principles of the subject but also, through selection of an option, allows teachers some flexibility to tailor the course to meet the needs of their students. The course is available at both SL and HL, and therefore accommodates students who wish to study physics as their major subject in higher education and those who do not.

Group 4 aims:

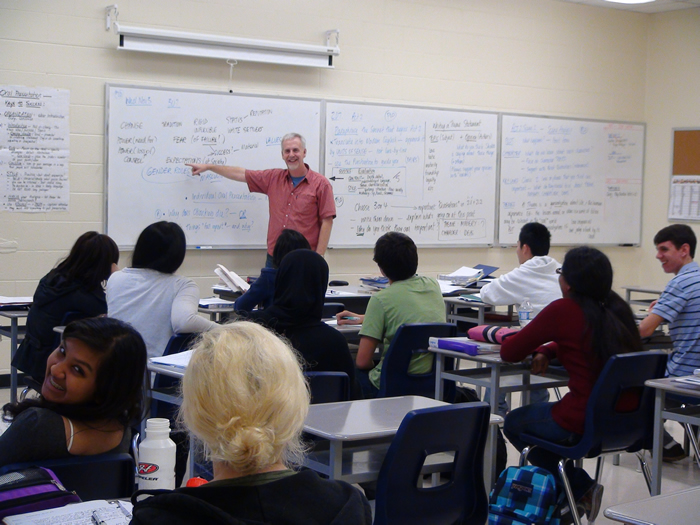

Through studying biology, chemistry or physics, students should become aware of how scientists work and communicate with each other. While the scientific method may take on a wide variety of forms, it is the emphasis on a practical approach through experimental work that characterizes these subjects.

The aims enable students, through the overarching theme of the Nature of science, to:

- appreciate scientific study and creativity within a global context through stimulating and challenging opportunities

- acquire a body of knowledge, methods and techniques that characterize science and technology

- apply and use a body of knowledge, methods and techniques that characterize science and technology

- develop an ability to analyse, evaluate and synthesize scientific information

- develop a critical awareness of the need for, and the value of, effective collaboration and communication during scientific activities

- develop experimental and investigative scientific skills including the use of current technologies

- develop and apply 21st century communication skills in the study of science

- become critically aware, as global citizens, of the ethical implications of using science and technology

- develop an appreciation of the possibilities and limitations of science and technology

- develop an understanding of the relationships between scientific disciplines and their influence on other areas of knowledge.

Science and Theory of Knowledge

The theory of knowledge (TOK) course (first assessment 2015) engages students in reflection on the nature of knowledge and on how we know what we claim to know. The course identifies eight ways of knowing: reason, emotion, language, sense perception, intuition, imagination, faith and memory. Students explore these means of producing knowledge within the context of various areas of knowledge: the natural sciences, the social sciences, the arts, ethics, history, mathematics, religious knowledge systems and indigenous knowledge systems. The course also requires students to make comparisons between the different areas of knowledge, reflecting on how knowledge is arrived at in the various disciplines, what the disciplines have in common, and the differences between them.

TOK lessons can support students in their study of science, just as the study of science can support students in their TOK course. TOK provides a space for students to engage in stimulating wider discussions about questions such as what it means for a discipline to be a science, or whether there should be ethical constraints on the pursuit of scientific knowledge. It also provides an opportunity for students to reflect on the methodologies of science, and how these compare to the methodologies of other areas of knowledge. It is now widely accepted that there is no one scientific method, in the strict Popperian sense. Instead, the sciences utilize a variety of approaches in order to produce explanations for the behaviour of the natural world. The different scientific disciplines share a common focus on utilizing inductive and deductive reasoning, on the importance of evidence, and so on. Students are encouraged to compare and contrast these methods with the methods found in, for example, the arts or in history.

In this way there are rich opportunities for students to make links between their science and TOK courses. One way in which science teachers can help students to make these links to TOK is by drawing students’ attention to knowledge questions which arise from their subject content. Knowledge questions are open-ended questions about knowledge, and include questions such as:

- How do we distinguish science from pseudoscience?

- When performing experiments, what is the relationship between a scientist’s expectation and their perception?

- How does scientific knowledge progress?

- What is the role of imagination and intuition in the sciences?

- What are the similarities and differences in methods in the natural sciences and the human sciences?

Examples of relevant knowledge questions are provided throughout this guide within the sub-topics in the syllabus content. Teachers can also find suggestions of interesting knowledge questions for discussion in the “Areas of knowledge” and “Knowledge frameworks” sections of the TOK guide. Students should be encouraged to raise and discuss such knowledge questions in both their science and TOK classes.

Science and the International Dimension

Science itself is an international endeavour—the exchange of information and ideas across national boundaries has been essential to the progress of science. This exchange is not a new phenomenon but it has accelerated in recent times with the development of information and communication technologies. Indeed, the idea that science is a Western invention is a myth—many of the foundations of modern-day science were laid many centuries before by Arabic, Indian and Chinese civilizations, among others. Teachers are encouraged to emphasize this contribution in their teaching of various topics, perhaps through the use of timeline websites. The scientific method in its widest sense, with its emphasis on peer review, open-mindedness and freedom of thought, transcends politics, religion, gender and nationality. Where appropriate within certain topics, the syllabus details sections in the group 4 guides contain links illustrating the international aspects of science.

On an organizational level, many international bodies now exist to promote science. United Nations bodies such as UNESCO, UNEP and WMO, where science plays a prominent part, are well known, but in addition there are hundreds of international bodies representing every branch of science. The facilities for large-scale research in, for example, particle physics and the Human Genome Project are expensive, and only joint ventures involving funding from many countries allow this to take place. The data from such research is shared by scientists worldwide. Group 4 teachers and students are encouraged to access the extensive websites and databases of these international scientific organizations to enhance their appreciation of the international dimension.

Increasingly there is a recognition that many scientific problems are international in nature and this has led to a global approach to research in many areas. The reports of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change are a prime example of this. On a practical level, the group 4 project (which all science students must undertake) mirrors the work of real scientists by encouraging collaboration between schools across the regions.

The power of scientific knowledge to transform societies is unparalleled. It has the potential to produce great universal benefits, or to reinforce inequalities and cause harm to people and the environment. In line with the IB mission statement, group 4 students need to be aware of the moral responsibility of scientists to ensure that scientific knowledge and data are available to all countries on an equitable basis and that they have the scientific capacity to use this for developing sustainable societies.

Students’ attention should be drawn to sections of the syllabus with links to international-mindedness. Examples of issues relating to international-mindedness are given within sub-topics in the syllabus content. Teachers could also use resources found on the Global Engage website

Group 4 Assessment Objectives

The assessment objectives for biology, chemistry and physics reflect those parts of the aims that will be formally assessed either internally or externally. These assessments will centre upon the nature of science. It is the intention of these courses that students are able to fulfill the following assessment objectives:

- Demonstrate knowledge and understanding of: a. facts, concepts and terminology

- methodologies and techniques

- communicating scientific information.

- Apply:

- facts, concepts and terminology

- methodologies and techniques

- methods of communicating scientific information.

- Formulate, analyse and evaluate:

- hypotheses, research questions and predictions

- methodologies and techniques

- primary and secondary data

- scientific explanations.

- Demonstrate the appropriate research, experimental, and personal skills necessary to carry out insightful and ethical investigations.

From Diploma Programme Biology, Chemistry and Physics guides, International Baccalaureate, Cardiff, Wales, 2014

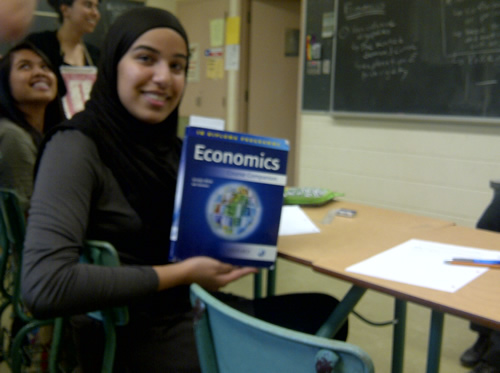

Economics is a dynamic social science, forming part of group 3—individuals and societies. The study of economics is essentially about dealing with scarcity, resource allocation and the methods and processes by which choices are made in the satisfaction of human wants. As a social science, economics uses scientific methodologies that include quantitative and qualitative elements.

Economics is a dynamic social science, forming part of group 3—individuals and societies. The study of economics is essentially about dealing with scarcity, resource allocation and the methods and processes by which choices are made in the satisfaction of human wants. As a social science, economics uses scientific methodologies that include quantitative and qualitative elements. Psychology is the systematic study of behaviour and mental processes.Psychology has its roots in both the natural and social sciences, leading to a variety of research designs and applications, and providing a unique approach to understanding modern society.

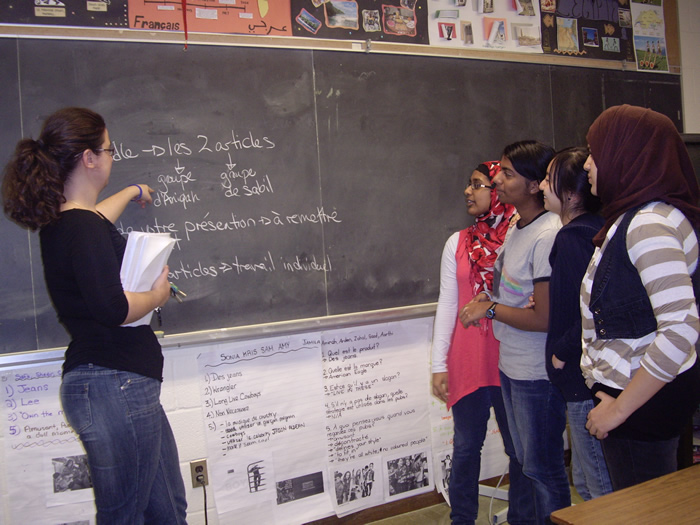

Psychology is the systematic study of behaviour and mental processes.Psychology has its roots in both the natural and social sciences, leading to a variety of research designs and applications, and providing a unique approach to understanding modern society. The course is built on the assumption that literature is concerned with our conceptions, interpretations and experiences of the world. The study of literature can therefore be seen as an exploration of the way it represents the complex pursuits, anxieties, joys and fears to which human beings are exposed in the daily business of living. It enables an exploration of one of the more enduring fields of human creativity, and provides opportunities for encouraging independent, original, critical and clear thinking. It also promotes respect for the imagination and a perceptive approach to the understanding and interpretation of literary works.

The course is built on the assumption that literature is concerned with our conceptions, interpretations and experiences of the world. The study of literature can therefore be seen as an exploration of the way it represents the complex pursuits, anxieties, joys and fears to which human beings are exposed in the daily business of living. It enables an exploration of one of the more enduring fields of human creativity, and provides opportunities for encouraging independent, original, critical and clear thinking. It also promotes respect for the imagination and a perceptive approach to the understanding and interpretation of literary works.